Please use the sharing tools found via the share button at the top or side of articles. Copying articles to share with others is a breach of FT.comT&Cs and Copyright Policy. Email licensing@ft.com to buy additional rights. Subscribers may share up to 10 or 20 articles per month using the gift article service. More information can be found here.

https://www.ft.com/content/262db450-e619-4397-a46d-cce6c8ec83a9

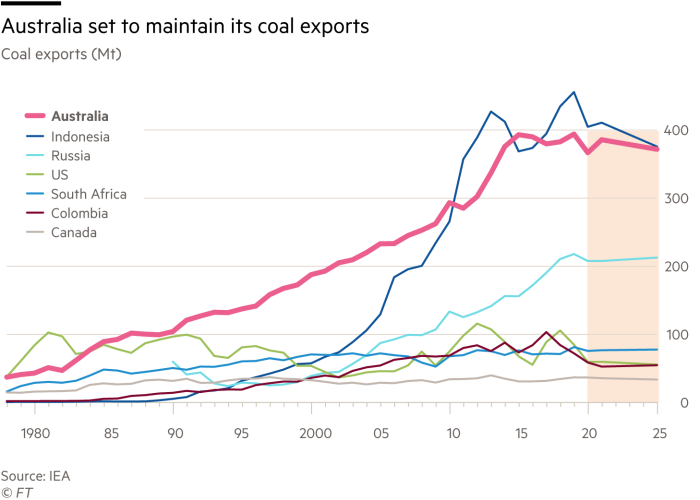

For more than 200 years, workers at the Port of Newcastle have loaded ships with coal dug out of nearby mines for transport to Asia and beyond. But with global action to tackle climate change set to decimate the trade, the management at the world’s biggest coal port is preparing for a future without the fossil fuel that generates 60 per cent of its revenues. “The future of coal is obviously questionable and we have to prepare for that,” says Roy Green, chair of the port, which is a gateway to the Hunter Valley, a coal mining region 280km north of Sydney. “We are likely to see a continuing flattening of coal volumes through the port and ultimately a decline, as the world switches away from coal-fired power.” The acknowledgment that coal, which is more polluting than any other fuel source, has a shrinking lifespan is an accepted fact in many boardrooms and mining communities in Europe, the US and China, where preparations for an energy transition away from fossil fuels are already under way. But in Australia, the world’s second-biggest exporter of coal by volume, discussions around phasing out fossil fuels remain contentious and risk inflaming the nation’s “climate wars” — a bitter 15-year battle between conservatives and progressives which has contributed to the ousting of three prime ministers in recent years. The government is resisting international pressure to commit to net zero emissions by 2050 and has ruled out charging polluters by setting a price on carbon. It opposes the early closure of ageing coal-powered electricity plants — arguing that relying too much on renewables could lead to power cuts — and recently funded a feasibility study on whether to build a new coal plant in Queensland.

Please use the sharing tools found via the share button at the top or side of articles. Copying articles to share with others is a breach of FT.comT&Cs and Copyright Policy. Email licensing@ft.com to buy additional rights. Subscribers may share up to 10 or 20 articles per month using the gift article service. More information can be found here.

https://www.ft.com/content/262db450-e619-4397-a46d-cce6c8ec83a9

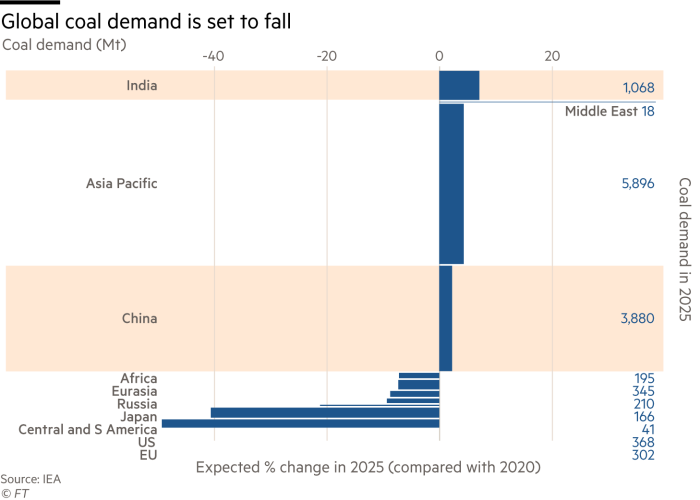

“We will not achieve net zero in the cafés, dinner parties and wine bars of our inner cities . . . [or] by taxing industries, that provide livelihoods for millions of Australians, off the planet,” Scott Morrison, Australia’s prime minister, told a business audience on April 20. Days later Morrison snubbed a request by Joe Biden, the US president, to join other nations in pledging deeper emissions’ cuts. Instead it is the decisions being taken by the world’s biggest coal consumers to commit to a net zero emissions target by 2050 in the case of Japan and South Korea, and 2060 for China, that could act as a catalyst for change in Australia, say critics. In a growing number of companies and communities across Australia, the discussion is changing from how to save coal to the need for a just economic transition to compensate for the loss of well-paying mining and related jobs. Many fear that if this does not happen, companies will go bust and people will suffer unnecessarily.

Please use the sharing tools found via the share button at the top or side of articles. Copying articles to share with others is a breach of FT.comT&Cs and Copyright Policy. Email licensing@ft.com to buy additional rights. Subscribers may share up to 10 or 20 articles per month using the gift article service. More information can be found here.

https://www.ft.com/content/262db450-e619-4397-a46d-cce6c8ec83a9

Energy Australia, a utility, announced in March that it would close a coal fired plant in the Latrobe Valley in 2028, four years earlier than originally planned. AGL, Australia’s largest utility, is also planning to split off an electricity generating division dominated by coal-fired power stations, a recognition that fossil fuels have fallen out of favour with investors. Some miners, including Rio Tinto and BHP, have either already exited the market for thermal coal — commonly used in electricity generation — or signalled their intention to do so. A collapse in price to $50 per tonne in the second half of 2020 due to weak demand linked to the coronavirus pandemic and import restrictions slapped on Australian exports by China have further raised doubts over the future of the Hunter Valley’s 40 mines, which support about 16,000 jobs. Critics warn there is an urgent need for Canberra to show leadership and plan an orderly transition to guarantee cheap and stable power, help coal mining regions diversify their economies into areas like agriculture and ensure Australia does not miss the opportunity to become a leader in green energies.

Please use the sharing tools found via the share button at the top or side of articles. Copying articles to share with others is a breach of FT.comT&Cs and Copyright Policy. Email licensing@ft.com to buy additional rights. Subscribers may share up to 10 or 20 articles per month using the gift article service. More information can be found here.

https://www.ft.com/content/262db450-e619-4397-a46d-cce6c8ec83a9

Yet Australia’s federal and state governments have in the past year funnelled A$10.3bn in tax breaks and subsidies to the fossil fuel industry. Almost three quarters of that came in the form of rebates paid to large users of fuel, such as miners and farmers, according to a report published by The Australian Institute, a progressive think-tank. Authorities have also approved an expansion of a Glencore coal mine just north of the Hunter Valley and an extra A$264m in funding for carbon capture storage — a technology that it hopes could extend the life of its coal export industry. “Australia’s foreign policy for decades has been to undermine other countries’ ambitions to reduce emissions so that we can continue to sell enormous amounts of coal and gas,” says Richard Denniss, chief economist at The Australian Institute. “Australia is not planning a transition away from fossil fuels. “What we are actually doing is trying to maximise profits in the endgame,” he adds. “That’s why there is a rush to approve new coal mines. We know that in 30 years’ time no one will be buying coal. But if we flood the market and push the price down, we can we can still sell some for the next 15 years.”

Please use the sharing tools found via the share button at the top or side of articles. Copying articles to share with others is a breach of FT.comT&Cs and Copyright Policy. Email licensing@ft.com to buy additional rights. Subscribers may share up to 10 or 20 articles per month using the gift article service. More information can be found here.

https://www.ft.com/content/262db450-e619-4397-a46d-cce6c8ec83a9

‘Money to be made in mining’ Any transition away from fossil fuels will be felt most keenly in places like Maitland, a blue collar city in the Hunter Valley which owes its rich architectural heritage to the profits generated in nearby coal fields. Four coal-fired power plants in the region are scheduled to close over the next 15 years, as energy companies begin phasing out their most polluting assets. Local coal miners will experience a modest drop in demand as a result of the closures, but of greater concern to the industry are the signs of slowing international demand for Australian thermal coal. Glencore and BHP, two of the country’s biggest coal producers, reported combined losses of just over $1bn in their Australian coal divisions in the six months to the end of December. In March, the Department of Industry warned that if exporters continued to receive lower prices for their coal due to Australia’s trade spat with China, production levels at higher cost mines could be cut. “There is so much pressure on coal,” says Gerard Spinks, who has worked in Hunter Valley coal power plants for more than 40 years, “that I think it’s going to disappear off the face of the earth in the not too distant future. It’s inevitable.” He was one of more than 100 people crammed into a bowling club in a Maitland suburb in March for the inaugural meeting of the Hunter Jobs Alliance, a collaboration of trade unions and environmental groups which wants to help the region prepare for life beyond coal.